As the influence that a brand’s heritage has increased in recent years, from design and product development, to marketing and collector relations, the role of those in charge of the archives and the company museum has become even more important. One such individual is David Seyffer, the Museum Curator at IWC Schaffhausen, with whom we were fortunate to have a wide ranging discussion on company history and its place in contemporary watchmaking.

Nicholas Biebuyck: How did you find yourself in IWC? What was your journey there? And when did you join?

David Seyffer: I joined in September 2007 and it was the perfect time because in that year the new museum opened, and the company was looking for someone who can take care of the archives. I wanted to start my historical research (at university) about IWC, so I asked to get access, and as a coincidence they also were very happy that someone with a background working in archives as a historian could take care of this job. This is how it started for me and it was perfect because I had the key to the archives, so whenever I wanted to go down, I could find new things to write about or check if this is worth implementing into the history or in my scientific work. So, it was really a good situation and then two years later, when my boss relocated to Brazil with his family, I took over the position as being responsible for the department. Since that point I’ve been here and it’s always interesting to see how the history is continuing.

NB: What was your academic background before? What were you studying?

DS:History and history of technology and science. I always wanted to learn more about ancient Rome, the Greek or early Middle Ages, but at a certain point I noticed the job opportunities in other fields, so this is why I changed to focus more on the history of technology. Around 2000, companies started to look for people or historians to help when it came to this topic, what they called history marketing. The first move was at the big automotive companies in Germany, also France and England, building up the historical departments, so being from Stuttgart, I started with Mercedes Benz, I think it was a completely new occupation for professional historians to work in the industry. Then with IWC, I really had the chance to learn and share what I gained to bring this into the world of watchmaking. For me, this was a really great experience to make history happen.

NB: I guess you’re in a very fortunate position at IWC, where you have this continuous string that the brand hasn’t been broken up or sold or messed around. With other manufacturers, they have these problems where the records might be thrown out so they need to rebuild everything from scratch, it seems that has really helped you quite a bit.

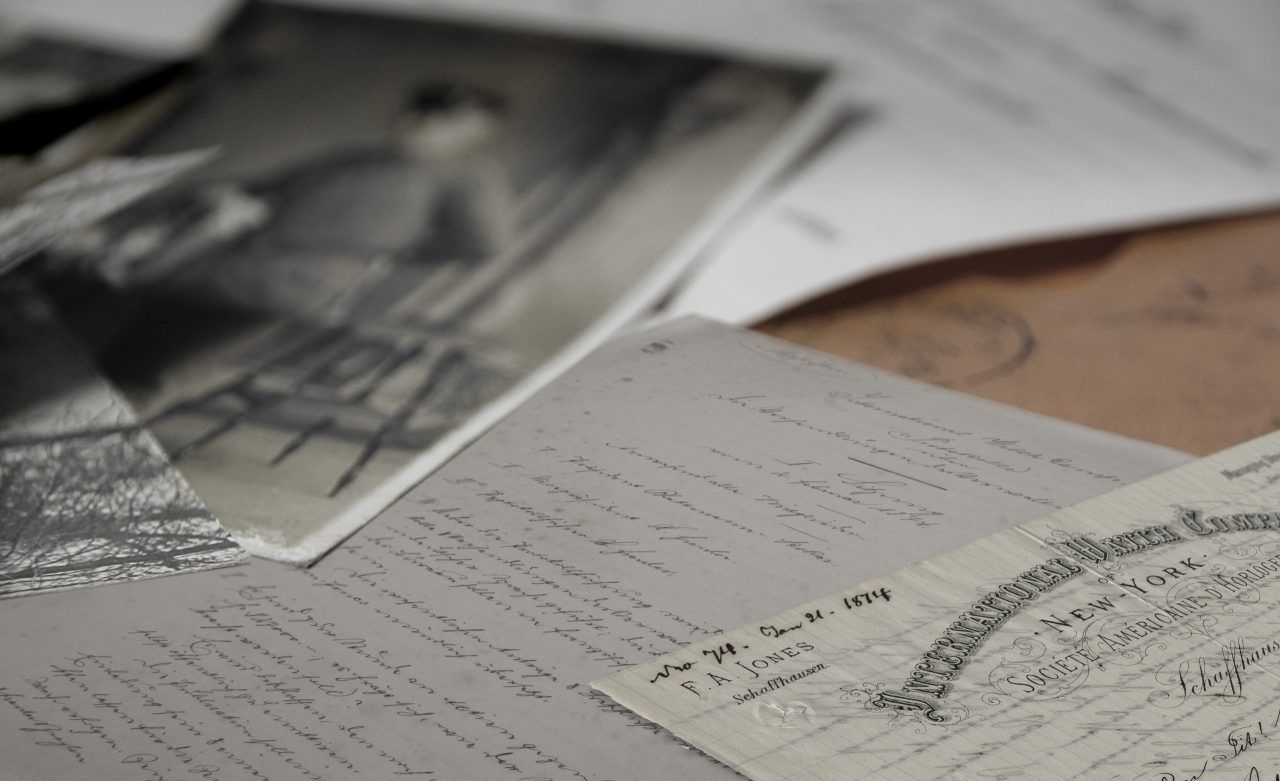

DS: To be honest, this situation also happened in IWC, in the 1970s, during the so-called “quartz crisis”, a lot of records were lost. So, this was really a challenge, but we managed to ask employees that have been around for many years if they have still, for example, catalogs or artifacts that could be really helpful. By asking the elder or retired colleagues, we happened to find interesting things that were missing in the corporate archives. We also started recording oral histories, making interviews with people, to fill in the gaps in the archives because of the crisis. Step by step, we managed to bring it back, which is now being very helpful.

NB: It’s amazing because you were at the beginning of this wave of archiving and preservation, for brands like Mercedes Benz and Porsche, thinking about how the reissuing of these parts has gone, that only happened in the last 10 years, and you were there a few years before even that started.

DS: I think in the future this will become even more important. If you talk to companies you would never think of, they have their own corporate museums, for example a small company, producing caravans, they have a really nice museum. Another company produces furniture for bathrooms, they have a museum and an archive. So this historic experience, it’s occurring in all different companies, and this is really nice to see.

NB: That brings us nicely onto the next question: where are the black spots in the archives, what is super complete and where are the gaps?

DS: IWC is really proud of what we have, i.e. the records of the watches, like the numbering of cases and movements, and this is very helpful because when it comes, for example, to certify the authenticity of watches, finding out the the history behind, when it was launched, these records are well preserved since the year of 1885 at IWC. What is missing? It’s not that interesting if you do storytelling for example, but all financial reports, sales figures over the years, which could be interesting to make a history of the performance for the company, sadly these things are missing. And also, correspondence from the CEO’s of all periods, so these are the gaps but as I said, if you check out other archives or you talk with people then you can get the picture.

NB: That’s really funny because with other brands it’s actually the other way around. They lost the case and movement numbers, the configurations and all this kind of watch-related thing. Because the financial records were with their accountants or auditors, and that’s what they have been able to get back. The interesting thing is since they had invoices from suppliers, questions like how many dials were produced, which design may have been ordered from Singer or other suppliers, were answered. So that’s how they’ve had to go back and reorganise the history. From the record, can you confirm what the case material was, what the dial configuration was, was it luminous, these sorts of information?

DS: With pocket watches, yes, we have the sales records, this is kind of an SAP system. We also have written books, from 1885 till the 1930s. For the pocket watch collectors, these are absolutely treasures, because then you can check, is this the dial that was originally fitted? And sometimes you find, for example, retailer or wholesaler signatures that you would not think of in the records, this helps to say if the watch is a hundred percent authentic. But with the later generations, in the case record books, there are some descriptions and information on the movements, but it’s not that detailed as it was in the 19th century.

NB: Hypothetically, if I come to you with a Mark 11 that has BOAC engraving, can you confirm whether that was shipped with BOAC or it’s been engraved later?

DS: To be honest, if you only look at our archives, it’s a little bit tricky. Only with more background information, we also got to talk to a lot of collectors, it would be possible. Through one of the collectors Mr. Thomas Koenig, who wrote a very famous article about the Mark 11, we had the chance in the late 1990s to go to the Greenwich Observatory, where they still have the records about the regulation and servicing for this market. And so, looking at our records of movements sold to the Royal Air Force in London, together with these records, then you find the pictures and then you may say if the Mark 11 was sold to BOAC.

NB: This is the fascinating part. I’ve experienced it when investigating issued watches for other companies or other organizations that you can see the batches, where they would send 50 watches to the UK to be given to the military unit, and you can see everything so much more clearly when you dig into the numbers.

DS: Military watches are always very tricky. For example, to issue something to the UK Ministry of Defense from IWC, you would need a British wholesaler, in our case Garrards, taking care of them for shipping the watches to the military. This may be the last black spot that we may need help from Garrards to shed more light on it, if they still have letters and sales records for these watches to the military, this is the last unknown territory, a project for the future.

NB: There have been some big steps in the museum since its establishment in 1993, such as the relocation in 2007, but have there been any other big milestones for you, such as a particular acquisition that made you very excited?

DS: In 2010 we became an official part of the Swiss museums’ corporation, which means we are an officially certified Swiss museum. This is quite important for me, and also for the whole team because it proves that the museum is not pure marketing only, but follows the international museum standards. We also want to be very open minded to other museums or researchers, also for students and kids if they need help to do something for school projects. This makes us very proud. Of course, every new acquisition for the museum, even if we can’t show it, is a very nice timepiece and always a milestone.

NB: When it comes to acquisitions, is it predominantly from private collectors or have you bought from auctions? Do you sometimes just get cold calls about watches?

DS: To be honest, 90% is from people who approach us. We have a budget and are looking for timepieces that can fill in the gaps. Very often people would proactively go to the museum and say, I have this old watch for example a 5253, we have enough, so to speak. Sometimes there are treasures, for example, there was a piece that had been in the family for four generations. The owner says, “I don’t like to sell it but if I can sell it to the museum and I know that it will stay there then I will sell it exclusively to you.” Maybe we are not paying the same price as a collector, but people are happy that for the future the watch will be safe and be appreciated. Auction market is also considered as a source, for example, for nice original Portugiesers, they come to auction from time to time, so then I act as a representative, to bid for the company.

NB: It wasn’t you that spent 60,000 CHF on a ceramic Günter Blümlein chronograph?

DS: The person who sold this watch originally offered it to us for 9,000CHF. The result they got from Phillips made him a little bit happier.

The IWC Big Pilot’s Watch Annual Calendar Edition “Antoine de Saint Exupéry” went under the hammer, garnering a winning bid of CHF 30,000 during Sotheby’s Auction in 2018.

NB: I had a lot of friends that wanted to bid on the watch, and they asked what I think they needed to budget. Honestly having heard all of the people that worked under him, who were so close to him, and wanted to have something to remember him by, I suggested spending like 25-30,000 CHF. I think the vendor was quite happy about the result.

DS: What was also very interesting is the whole story. When you look at the auction market today, it’s like art: when you have good documentation about the watch on what has happened, for example if this watch was sold to any dealer from the family of the original owner, and you can prove it, it makes it more interesting. In my personal opinion, in the future, collectors will be interested in watches that have this kind of personal story. If you can have the proof or if you have the evidence from the archive to make the statement, it’s good for the brand and also for the auction house.

NB: It’s something we’ve been talking about a lot recently, since the mid 1990s to mid 2000s when the auction market started to pick up, everyone was very focused on rarity and we saw a lot of counterfeiting of retailer dials and the like because people want the watch to be rare. Following on from that, condition became everything: everyone was obsessed with the condition. Now what everyone wants is provenance, they want clear history from the original owner until now. It’s the same in the car market, the same in the art market and it’s finally reaching the watch market. When we have all three together, that is the situation where we see incredible results. It’s going to be interesting to see how it plays out and see what part the archives have to play in this, because that has helped a lot as well.

DS: Not only the archives but also the service departments. As a service department, at IWC or other brands, you always want to provide the customer with a perfectly restored watch, that is as close to the original look that’s working. For example, if my colleagues do a service for Mark 11, you will get the guarantee that it works for two years, but in some cases, the collector says they don’t want to wear it. Personally, I liked to wear watches; let’s say you have a vintage car, for example, a DB5 Aston Martin, it would be nice to take it for a ride. Maybe not daily rides, but at least keep them running. And the same with watches: to put it in a drawer and have it as an investment piece, it’s not my world.

NB: I’m a firm believer in the fact that these things are meant to be used. I wear vintage watches very regularly, you just have to be a bit more mindful about them. The big challenge at the moment is that there’s so many new collectors coming to the marketplace. I have a friend who bought a Mark 11 on my advice, from the Royal Australian Air Force because he’s Australian. He wore it for a week and it stopped working and I said, can I take a look? And he had clearly smacked the watch against a table or similar, and the problem is, when you’re so used to wearing a contemporary watch, which is engineered to handle all of these kinds of impacts, when you switch to a vintage watch, it requires a slightly different mentality. There’s a need for training, but absolutely, these watches should be worn and enjoyed.

DS: Handling vintage is very tricky. For example, the Pallweber watches in our history; they can be working, but you have to take care of them even if you’ve got the guarantee from the IWC service department, you still need to be very careful.

NB: Another compelling point is that, in the car market, everyone is so much more comfortable with the idea of restoration, whereas the watch market is almost entirely about preservation at this point. So, it’s going to be really interesting to see how that that plays out going forward. Before we go on to specific models, can you share a bit of the history of Albert Pellaton, the winding system and his relationship to IWC?

DS: Albert Pellaton was born in the western part of Switzerland, worked for Vacheron Constantin and Omega, and then, when promoted to be technical director for IWC in 1944, found himself very comfortable in Schaffhausen. It’s very interesting to see in the 1940s, everybody was looking for the perfect self-winding system or automatic system in watches. Some experimented with small seconds and then the center second became very popular during the Second World War. On how he solved it, we have some drawings of his with the caliber 89, the first automatic winding system he created. The outcome was really interesting, it was a breakthrough. Of course, Pellaton was not only in charge of the production and the processes, which is a management position, but also he was the watchmaker. A lot of the older colleagues were telling us, when they started to work for him, he was always saying if you want to work in production, I want to check your skills, so he gave them a movement and asked them to do some things on it, just to understand if they could perform as a good watchmaker, he was very picky on hiring them. On the other hand, he organised the production on a large scale and managed perfectly. This is the very unique part of Albert Pellaton.

NB: I’ve not thought about that actually. His experience in raw design, engineering and watchmaking, actually helped a lot when it came to management, understanding another side of things, very valuable skill sets. Can we talk a bit more about the Mark 11, its applications with the military and also how the calibre 89 came about? Why is it so highly regarded for IWC?

DS: The interesting thing for the Mark 11 is that the military requirements were first, and then it was to have the caliber 89 for that watch. A couple of months before, we had an interview with an old watchmaker for the British Air Force, who remembered the discussions in the 1950s. The company Smiths, at the time, also wanted to meet the expectations for the Mark 11, but sadly the watch was not good enough for the Royal Air Force. With Jaeger-LeCoultre, the movement was tricky because the robustness was missing, compared with the caliber 89. At the end of the day, the preciseness and the robustness were the key points for them so it was a perfect match. We were very happy that it was first designed for the civil market as a very high quality and precise caliber. But also because of Mr. Pellaton’s characteristics made the watch meet the expectations of the Royal Air Force. Even in extreme conditions, when you are flying, your aircraft is bumping around, it’s still running precisely and this is the most important thing when it comes to navigation.

NB: When we think of materials for IWC, the ceramic in the Fleigerchronograph and the titanium in the Bund, how did IWC find itself in a position where it was so pioneering in its use of materials in watch applications?

DS: To be honest, these innovations were the result of the crisis in the 1970s, when the suppliers, very important or very famous case makers that not only IWC were working together with, had to cease the production in the 1970s, so we had to find other solutions. The management, for example, Mr Lothar Schmidt who is now the owner of Sinn, had the background of case making and case constructing, so the idea then was to try new things, to be innovative and to make the brand interesting. This led to this very weird situation in the early 80s, when visitors came to IWC, they said “you are famous for watch movements, but where are the watchmakers working? I only see case production of titanium and other materials?” It was only the situation because movements were from ETA, who was very happy that someone was there for the 7750 and 2892 movement, because there was no market for these mechanical calibres. Also we worked with Porsche Design, Ferdinand Alexander Porsche was really pushy for the black watch that he wanted and was very happy with the titanium case. It is completely a result of the crisis, and of course in this traditional business of watchmaking, it was very important that you are willing to take the risk to do something new and get out of this whole crisis. This is also why IWC is very successful now, it was a gamble, the choice was an option. On the other hand, the plan B was to stay very conservative and stay with vintage complicated pocket watches, to please at least a small number of collectors, and this combination helped them to make the Da Vinci and Pallweber collections.

NB: When titanium and ceramic were being used, how were you even able to find suppliers for these materials, especially ceramic? Because they were such pioneering materials at the time.

DS: The interesting thing with the ceramics is that it was completely a Schaffhausen project. We have to be very careful, because ceramic is not ceramic, we are talking about the zirconium oxide which is the ceramic we use and not like other Swiss brands, those are another material. To be honest, those were a little bit earlier, with the IWC ceramic, we were the first mover. Starting in 1977 in Australia, the first prototypes with this material were made, and so it was Schaffhausen company, Metoxit, that was looking for products that can be realised with this material. So they thought maybe it would be good for automotive or dentistry, as it was hard like steel, but to make the material more popular the idea emerged to make watch cases from this material, then the whole project for Da Vinci started, so it was really a joint venture. The management team of Metoxit were very happy, as they could now offer this material into the world of luxury. It’s very interesting if you look at the marketing material from this company, they have the Da Vinci from 1986, even though they wanted to sell the material to car companies. For IWC it was also a big step because everyone was used to gold or stainless steel in the world of luxury and now they came up with the ceramics; this technical approach was very appreciated by clients of IWC. The funny thing is that our customers don’t want different colors other than black, this is also why with the Top Gun family, the black ceramic (made from black zirconium oxide and titanium) IWC Fliegerchronograph is kind of iconic.

NB: I’m so glad the reference 3705 is a moment in the spotlight, because actually the first time I came across this watch was about 15 years ago. And when you put it on your wrist, it’s such a different experience: the mass of the watch and the way that it conducts temperature and the way that it feels against your skin it’s so different from any other materials. So, it’s wonderful to see it having people respecting it in the way that it should be.

DS: The original product name, or let’s say project theme, was Mark 12 chronograph ceramics.

NB: Going back now, talking about the reference 325 of the original Portuguese, how did it come into the market and what are your preferences when it comes to configuration?

DS: This is a tricky question because to be honest, we do not know the master plan. What I know is a bit of a different story from a private collection, where there are two of the very first Portugieser and the dials look authentic. We can say that the look of the first generation of Portugieser, that were sold in 1939, is what we are promoting. To be honest, although it was a pocket watch movement, contemporary dials were also available. The variety may also be found in the auction market. I was very fascinated when I saw, for the first time, a Portugieser with radium numerals; we checked the watch and it’s authentic. And also, the one with Louis XV hands, showing the taste of the late 1970s, this was the kind of the third generation of reference 325 that was especially made for the very niche collectors’ market. They wanted to bring more of the traditional aspect of pocket watches into the “first pocket watch for the wrist”. They chose the dial fits for the Calibre 74 (pocket watch movement), and then they made it happen.

NB: Just going back a little bit, the retailers in Portugal basically requested this specification for clients, that’s how the watch came into the market, right?

DS: This is an interpretation of the sources. We know that Rodriguez and Teixera were actively starting to buy watches in Portugal in the 1930s. Portugal was a gap in our retail landscape, in the situation in the 1930s, the most important markets were Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic. We had to find new markets because IWC were in these territories that were occupied by the Germans. We had no chance to sell the watches there, so we were looking for new markets and Portugal seemed to be very interesting, when the aggression of the German and also the other Fascists started. In this period, you find a lot of orders from Portugal, this is what brings us to the idea of offering these huge watches to the Portuguese market. Some Portuguese collectors remembered when they were young, seeing these huge wristwatches on many lawyers’ wrist, all of this makes sense. Also, given the war situations, how to get these watches out of Switzerland was very interesting; it was not until 1942 that the first Portugieser went to Portugal. IWC kept up selling these watches to Portugal till the 1950s, and then for some reasons, in the late 1950s, there were no further shipments to Portugal for these watches.

The reintroduction of the reference 325 started in the 1970s. It was during a board meeting when Mr. Homberger said people wanted to have these old watches, we shall make it happen, but with a new kind of movement like the caliber 982 with a shock protection and without shock protection in the caliber 98. And this was the story of the missing link, like the collectors called it. I think it was around ninety or a hundred watches that were sold to Germany in just three years. It really amused me because these watches were the inspiration for the 1993 collection of Portugieser and the story of success.

NB: That leads us on quite nicely to the launch of the Portofino in 1993. Please explain to us what the position of the company was at that stage and what the launch meant then?

DS: With Portofino, we have to go back in the 1980s. In 1984, the first so-called Portofino line was launched, which is interesting because it’s linked to what we discussed before. The perception of IWC in the early 1980s was materials, like Porsche Design, which are not classical watches, like those were famous in the 1950s and 1960s. There were complaints from customers, saying “I want to buy a really classic gold IWC, but you do not have something in the inventory”, so the decision was made to build a collection to meet these expectations.

We built up the Portofino collection as the elegant representation. The marketing director in those years, Mr. Hannes Pantli, was a fan of Italy and Italian lifestyle. He made the best decision by naming the collection Portofino, because you can spell this word all over the world and only by naming Portofino, you are already in this kind of Italian mood. It completely explained the background of this family. In records, there were also some other options for the naming, like, Amalfi chronographs, the Romana or the Venezia. The Portofino was the one we used since 1984 and became an important part of the collection.

NB: It’s amazing to talk about these different models and like cutting up IWC into these blocks of different references, because it goes to show how diverse the company was, like a chameleon whenever the market changes.

DS: In Chinese, there is a saying, whenever there is a crisis there is always a chance. If you look at the watch industry, especially for IWC, this is very true. Because there were so many crossroads, sometimes we went only one way, but sometimes we tried to go different ways, it helped us to establish these kinds of collections. Only in the 1980s, the company restructured the whole collection and made it understandable, putting together all the elements we made before.

NB: Obviously Schaffhausen is a long way from Geneva. Do you think being in a different part of Switzerland has helped the brand to think differently, evolving differently during these challenging years, especially around the quartz revolution?

DS: Absolutely. Sometimes the connection is good, such is before the 1970s in the watchmaking industry. There was a kind of trust within the whole Swiss industry, the federations of watchmakers. They had really harsh and strict policies, it was not very helpful when you wanted to be invited. There were some rumours about a project by Mr. Pellaton, the famous caliber 70. The production was very straight forward, but they say it was once stopped because it was too innovative for the watchmaking industry.

In fact, in the 1970s we were far away, and everybody was looking how IWC would survive the situation. We have this freedom, that we needed, to bring titanium or the new materials to do this kind of innovative project. Because before, it would not have been so easy to make this happen, so the distance created the character of the watches. What has happened in the last 20 or 30 years, it was good that we have this 200 kilometer distance, to bring the characteristics inside IWC watches.

David Coulthard (left) and CEO of IWC Schaffhausen, Christoph Grainger-Herr (right), at Goodwood, 2018.

NB: On the relationship between watches and cars, especially given IWC’s partnership with Mercedes AMG, is it a historic connection? Do you find evidence of IWC being involved in the automotive landscape in the early 20th century and why do you think the two disciplines are so close together?

DS: That’s a good point. There is a pocket watch from 1910 or 1912, it was made for the French market, showing four people sitting in a car, so this shall be the first connection. To be honest, it was not kind of a strategic work together with the automotive industry or as a partnership, as we would call it today. Interestingly, Mr. Pellaton, not for IWC but for another famous Geneva company, invented a time measuring system for Formula One in 1936. There was a connection but not a relationship that started in the 1980s when it was noticed that people who like vintage cars, also like watches and vice versa. And so this idea was coming up and we were one of the first companies to work together with classic rallies or vintage car races, which led us to cooperate with Mercedes-AMG. The match was perfect as the approach between two brands emphasises both performance and design. Historically, some car drivers or racers had IWC on their wrist, which is not as a strategic approach as the one with AMG-Mercedes now.

NB: Can you talk about the retro-revival movement that is taking place in the watch industry right now? And how do you think it will define the museum role going forward with product development?

DS: IWC always looks for inspiration from the past. Sometimes the characteristics from the past are more important and sometimes they are not. The collection we launched in 2008 was the vintage collection for the first time, what we called Retro-revival. It’s not like the design team brought the retro to make it appealing to customers. It’s as if you grew up seeing a typical watch that your seniors were wearing, and now you want to buy the watch, but you can’t find the vintage ones. It’s the nostalgia that drives the retro-revival. Because of these stories in the 1960s and 1970s, this is helpful to stay true with these design codes to make it look alike. This is also a good statement to say, IWC stays true to our design codes and brand history.

NB: Do you have many design or engineering teams coming down to the museum and archive to check information?

DS: The design team once asked us if they can have the original watches for their meeting. They don’t just want the two-dimensional concept but also touch and feel the watches, e.g. how the polishing was made, the feeling of different dimensions. Then they would decide to stay with the design or make something different.

NB: When the new HQ was developed in the last few years, were you and the museum team involved in that site? Has it had much impact for you?

DS: The Manufakturzentrum to us, is how you can help the manufacturing of watches and the assembly line at its best. I learned from the CEO, what is interesting is that the building is inspired by Ludwig Mies Van Rohe at the World Exhibition in 1921, and it was also a coincidence that IWC won a prize at this world fair. If you dig very deep into the archive, everything fits perfectly together.

NB: I found it very interesting that your CEO Mr. Christoph Grainger-Herr’s background is in architecture and how he implemented these ideas within the Manufakturzentrum, like this multidisciplinary approach. And from your side, you are an archivist and curator, it goes a great way in telling the complete story of humans and its relationship to engineering.

DS: We are in the lucky position that we can keep up this old tradition and make it appealing to younger generations, and therefore, it’s good that you have multiple sources to back up the narratives.