Although the modern equation might appear to have Swiss watches on one side and great examples of horology on the other with a pronounced equals sign in the middle, it is not only the landlocked nation that has participated in the technological advancement of watchmaking. The rest of the world has also demonstrated remarkable vision and contributed a great amount to horological culture. In this second instalment on the geography of the industry, we will be discussing some notable names and regions outside of Switzerland, for a brief historical rundown of international horology.

Timekeeping in Western Europe

Watches have come a long way since the original concept of timekeeping. If we go back in history, the first devices to record the passage of time consisted of water clocks and sundials, before measuring time became increasingly important in the 14th century, particularly in Western Europe where religion required regular prayers throughout the day. As clocks were not made available to one and all, being reserved for the wealthiest due to their vast expense, the public had no way to tell the exact time due to the ever-changing pattern of natural daylight throughout the year.

Instead they would rely on the church, who had sufficient funds to afford the construction and maintenance of a clock tower, announcing the time for prayer all over the towns and cities with their striking bells. This way, not only the faithful could make their dedications to the almighty, but the commune could function on a regular schedule. However, the timekeeping device from the period had a high margin of error, as it was not built for precise timekeeping in comparison to later times, but it was adequate in serving its purpose.

Precision would improve rather quickly during the 17th century, when the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens invented his famous oscillating mechanism, the pendulum, thus vastly reducing the error for clocks from at least 15 minutes per day on a verge escapement to just 10-15 seconds per day. He also developed one of the first functional examples of a balance wheel equipped with balance spring (developed at the same time although independently from Robert Hooke working on the same concept in England), and the invention of both mechanisms focused on improving the chronometric performance.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and there are increasing numbers of watchmakers scattered throughout the world that dedicate themselves to creating amazing timepieces, thanks to the educational institutions in Switzerland and elsewhere. Horological culture is spreading and initiatives are available internationally, for those who are dedicated. The Grönefeld brothers (Netherlands), Stepan Sarpaneva (Finland), and the McGonigle brothers (from Ireland), are some of the successful examples of modern watchmaking careers based outside of Switzerland.

The Marine Chronometer by the British

The invention of the marine chronometer in 1735 was a significant step in horological history. Before that, sailing was simply dangerous, as navigating was difficult due to the inaccuracy of maps and geographic coordination systems of their times. However, due to political and commercial imperatives, jobs usually came with lucrative rewards, leading to people being willing to risk their lives, despite the tough conditions on a boat with unsavoury meals and the unpredictable environment.

During the voyage, latitude was estimated by the position of astronomical elements (stars, sun and moon), while longitude could only be calculated with speed and the difference from local time, and was widely inaccurate because of the changes of wind and current. The error of geographical position in sailing was highly fatal, and had caused numerous unfortunate disasters at the sea. It was so problematic that following Spain, the Dutch, French and British all announced a reward for a way of determining the longitude with a reliable degree of accuracy. The British offered a sum of 20,000 pounds (equivalent to 7.5 US million dollars at the time of writing,) to whoever figured a way of finding the longitude within 1 degree. After two decades, John Harrison, an English horologist, invented the spring remontoir and the first practical marine chronometer that finally opened the gate to more precise maritime navigation. In terms of watchmakers in the modern days, there was the legendary George Daniels, and his dedicated successor Roger W. Smith, who is still following the traditional English way of making watches, inside a tranquil workshop located on the Isle of Man.

The French Pursuit of Accuracy

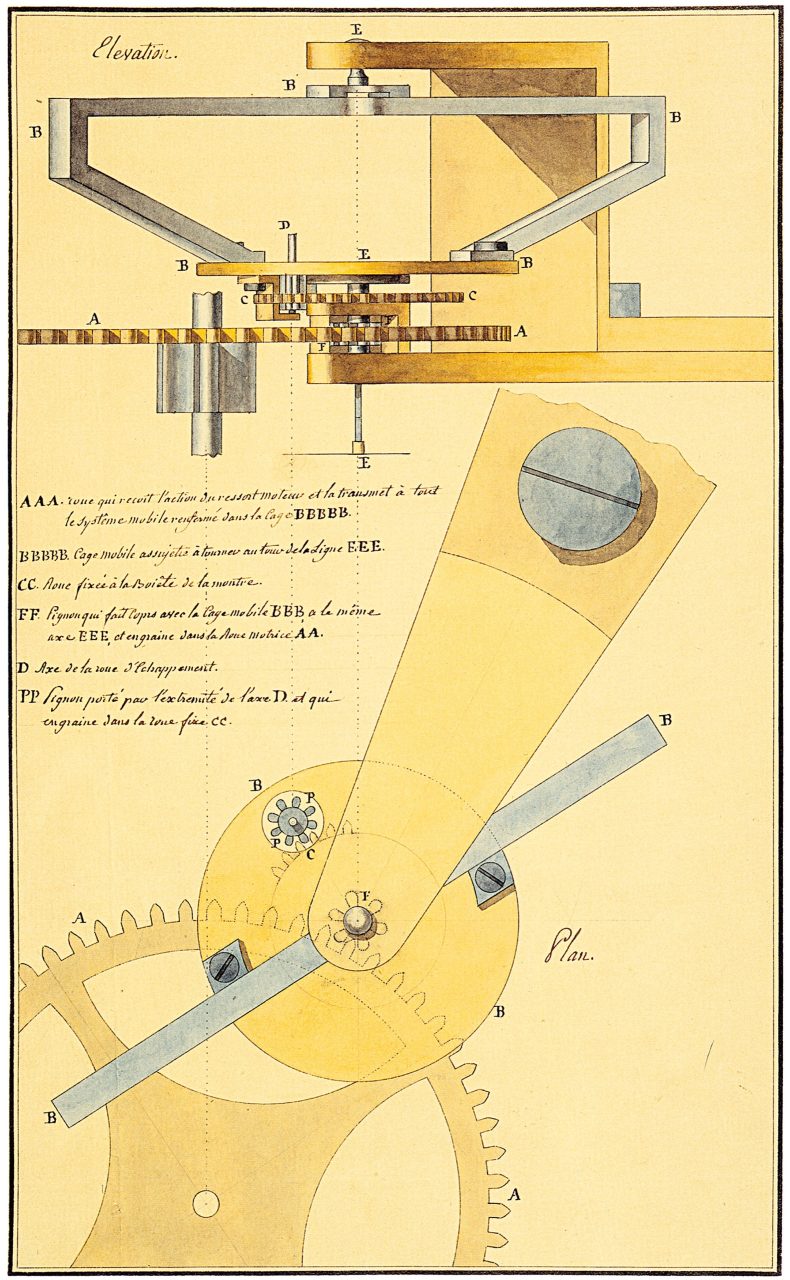

As society became increasingly civilised, the standard of punctuality became higher as a form of acquired manner, and so timekeeping devices needed to improve as well. In the beginning of the 18th century, French horologists would further extend the boundaries of accuracy with multiple inventions. For instance, succeeding the work of John Harrison, Pierre Le Roy adopted his invention in constructing a chronometer with the detent escapement and compensating balance wheel, which reduced the error on the balance wheel from thermal expansion, while achieving isochronism.

For the ingenious Abraham Louis Breguet, he contributed to the world of horology with his numerous inventions, from oscillating elements such as the overcoil balance spring and tourbillon, to the refinement of time-telling mechanisms such as the chiming gong and retrograde display, his creativity found him great success in the watch business, serving royalty and other well-heeled clientele.

Although many of the craftsmen eventually migrated to Switzerland, there are brands in our time that still possess a high degree of Frenchness within their timepieces, such as Cartier, Van Cleef and Breguet; their historic decorative traits coexist with the relevant horological details in their modern timepiece. For brands within the French border, Yema may have changed hands over the years but remains proudly French, with an in-house calibre produced locally in Morteau, and there are new talents such as independents Charles Routhier and Rémy Cools, who demonstrate impressive architecture and design on their timepieces.

Industrial Revolution – America vs Switzerland

For better or worse, the Industrial Revolution inevitably impacted the world of horology. The introduction of new manufacturing technologies encouraged a standardised mass production process applied to numerous products, with no exceptions on clocks and watches. Suddenly, pocket watches that were once reserved only for the wealthy noble class became domestically available for a much cheaper price, thus much more profitable from a business perspective due to a lower production cost and considerably wider accessibility.

It was quickly adopted by the Swiss and American watchmakers. The craftsmen around Europe, who refused to jeopardise the integrity of horology, would slowly fade away due to the ongoing race for the market between both countries. America eventually lagged entering the war period, leaving Swiss watchmaking as a virtual monopoly.

There are now a few passionate independents residing in America, including the self-taught guilloché artisan and watchmaker Joshua Shapiro, who subsequently supplies his guilloché dials to another local clock and watchmaker, Daniel Walter, while there are a few brands like Shinola, based in Detroit, who source their movements elsewhere but assemble in the USA.

The War & Post-War Period – The Soviet Union

Time-telling devices drastically changed during the war period. The functional necessities on the field completely overtook the more fashionable perspective of wearing a wristwatch. The design also became more robust and utilitarian looking, as seen on chronographs with telemeters and luminous dials.

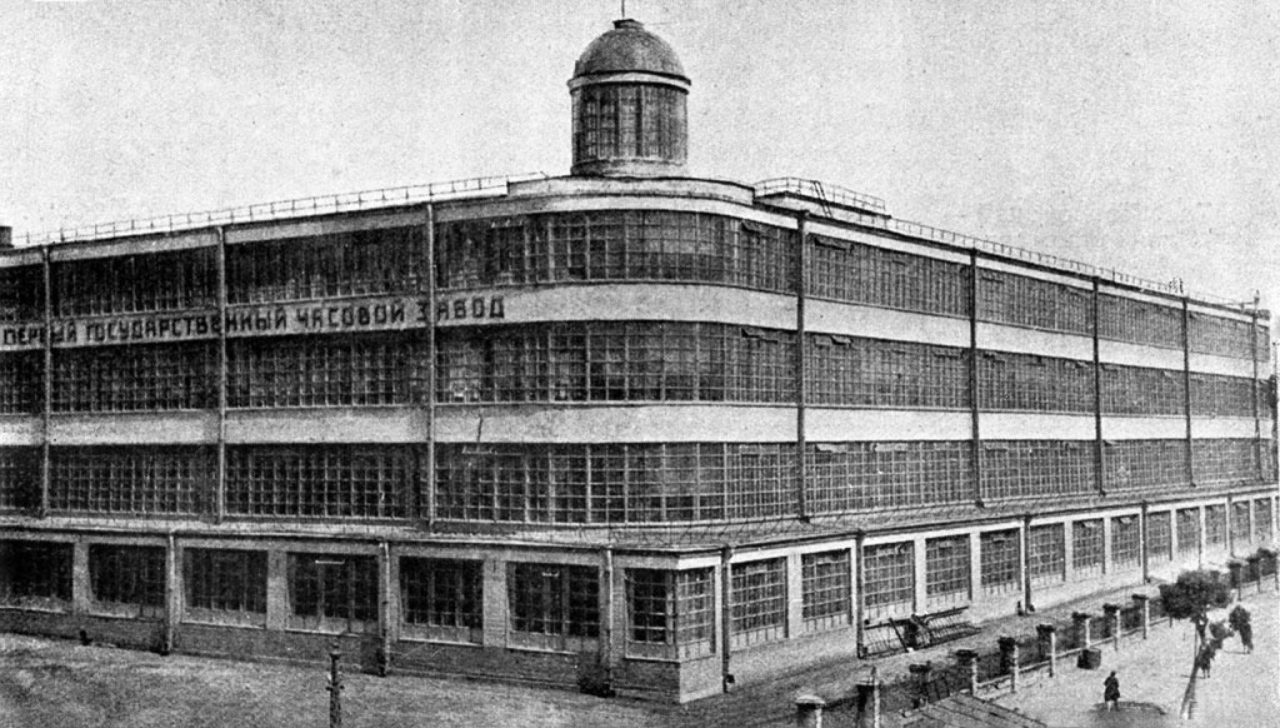

Interestingly, the wartime also led to the rise of Soviet industrial watchmaking. Though local independent watchmakers were not found until 1927, they began manufacturing watches on an industrial scale. In 1930, the Soviet government offered to buy out all the patents and equipment of the Dueber-Hampden Watch Factory in Ohio, America, which was bankrupted because of the recession in their pocket watch business. Together with the assistance of 21 American employees, the First Moscow Watch Factory (Poljot) was set up and ready for production in the following year, supplying primarily the Soviet government and the Red Army, accompanied by small numbers of civilian pieces. Up until 1990, the First Moscow Watch Factory produced up to five million pieces a year, with names such as Poljot and Strela on the dial, but the Soviet watchmaking industry would eventually shut down, including the First Moscow Watch Factory, during the fall of Soviet Union.

Though watchmaking is no longer a major industry in Russia, there are brands from the similar timeframe of Poljot, such as Vostok and Rekata still manufacturing movements and watches. In addition, there are keen watchmakers such as Konstantin Chaykin, an independent devoted to his work to the Russian watchmaking industry. Being the only Russian admitted to the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants, his creative approach creates a rather unique aesthetic of his own.

Quartz Crisis, Japan vs Switzerland

Japan is one of the countries in Asia that possesses the most horological heritage. Mechanical timekeeping started replacing clepsydra, or water clocks (which can be traced back to the Edo Era around the beginning of the 17th century), when Christian missionaries passed on the knowledge of making clocks and other astronomical instruments. With influences from western culture, the horological development and business quickly took off.

In the middle of the 19th century, clocks and pocket watches were readily available, and dealers and shops were quite popular among the Tokyo area. Kintaro Hattori, who acquired his knowledge and skill of repairing timepieces through multiple apprenticeships, decided to start a business in selling and repairing watches and clocks in Ginza, Tokyo, in 1881. Eleven years later, aided by the economic upturn, he established the Seikosha factory with a dozen employees. The venture grew rapidly into a modernised factory with advanced technology, establishing the fundamentals of the company now known as Seiko.

During the post-war period, Japan went through a tough recovery from war damages and aimed to become the “Swiss watchmaker of the East”, they would eventually achieve so by competing with Switzerland in the famously known “Quartz Crisis”.

While having an electronic oscillator in timekeeping devices was not a new concept at the time, the first wristwatches with quartz oscillators did not appear until 1967, in which both Switzerland (Centre Électronique Horloger) and Japan (Seiko) presented their own timepiece. Just two years later, Seiko would later come up with an analogue quartz watch with a superb accuracy of +/-0.2 sec per day, which was 100 times more accurate than a fine mechanical movement and revolutionized the horological industry worldwide. Switzerland did not keep up on the technological front, and in just 10 years, Japan dominated the market and surpassed the 100 million count of both clocks and watches produced and exported by the end of 1979.Since then, Japan has steadily advanced and increased their market with renown brands such as Seiko, Orient, Citizen, Casio. Japan has also embraced the return of mechanical watchmaking, with up and rising independent watchmakers, such as Hajime Asaoka, and Masahiro Kikuno, and Grand Seiko also taking tremendous pride in the skills and artistry it has developed over the past few decades.

Since then, Japan has steadily advanced and increased their market with renown brands such as Seiko, Orient, Citizen, Casio. Japan has also embraced the return of mechanical watchmaking, with up and rising independent watchmakers, such as Hajime Asaoka, and Masahiro Kikuno, and Grand Seiko also taking tremendous pride in the skills and artistry it has developed over the past few decades.

Revival of Glashütte, Germany

Glashütte, before its watchmaking fame, was a small town in the state of Saxony, in a region with rich ore deposits. It attracted many miners and consequently leading to the growth of its population and economy, and was once a rich and vibrant town until the mines were exhausted. At this time, Ferdinand Adolph Lange, who studied and acquired his watchmaking knowledge in Dresden under the guidance of Johann Christian Friedrich Gutkaës, was a skilled watchmaker with entrepreneurial ambition. He long envisioned a watchmaking industry for his home country that could lower the need for watch imports, and the depression of the town came in coincidentally as an opportunity, which he seized in proposing his plan to the Saxony government, convincing it in 1845 to give him a loan to bring watchmaking into Glashütte. Starting with only 15 apprentices, he built the industry step by step, designing the machinery required for manufacturing pocket watches, transferring dimensions into the metric system, and training local farmers into watchmakers. During that time he also developed the three-quarter plate which later became the signature of any Glashütte timepieces. Though with great effort, the process was slow and challenging, but his persistent mind led his way through the tough times and established a firm base for the Glashütte watchmaking industry.

After World War II, the watchmaking industry of Glashütte was expropriated by the Soviets, and all the watchmaking companies were combined into the VEB Glashütter Unhrenbetriebe (GUB), which remained until the fall of the Berlin wall. Ferdinand Adolph Lange’s great-grandson, Walter, saw an opportunity to revive the brand and with the help of the late Günter Blümlein, was able to re-establish A. Lange & Söhne in 1994. Glashütte today counts numerous brands such as Glashütte Original (which is technically what the GUB became when it was privatised in 1994), Nomos, and Moritz Grossman, to name just a few.

Closer to Home

China was also a country famous for using clepsydra to keep time in ancient times, but the missions of the Jesuits in the 17th century opened the door to introducing western timekeeping technology and styles to the Middle Kingdom. Though at first seeming reluctant, the Chinese had soon found out the convenience brought by the intricacy of mechanical clocks and watches, not to mention their appreciation as high value objets d’art, and continued to import and purchase horological instruments from the Western countries, mostly exclusive to the Emperor and his dignitaries. Local watchmaking industry did not fully emerge until the Chinese Revolution took place in the early twentieth century, when the Georgian system began to coexist with the Lunar system and was slowly adopted by the general public.

In terms of watchmaking as a local industry, it was not until China entered the Mao era that it began to rise. During the 1950s, when consumerism was strongly promoted within the country, there were the “three great things” that were highly desirable among citizens following their daily necessities: bicycles, sewing machines, and, of course, watches. At the time, China lacked the capacity and technology in manufacturing timepieces entirely locally, which consequently led to the dependency on imports from around the world until the local watchmakers learned from the Swiss and Soviet mechanisms, after which the production quickly expanded as factories were established across different regions of China.

One of the original factories from the ‘60s, the Tianjin factory, was responsible for manufacturing aviator chronographs for the People’s Liberation Army Air Force, as well as pioneering the development in some of the earliest “in-house” Chinese movements. The factory continues under the name Sea-gull as one of the well-known brands from China, not only making their own watches but also manufacturing ébauches for third parties. Other than Sea-gull, Fiyta is another proudly Chinese Brand that has adopted a rather unconventional model where parts manufacturers, assemblers and brand owners exist as independent entities to form a dynamic production chain.

As for the independents scene, the late Kiu Tai Yu was a talented watchmaker, and the first Asian member of The Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI). He produced the first tourbillon wristwatch in Asia, and in his later work, namely the Mystery Tourbillon, he cleverly integrated a sapphire crystal disc as the tourbillon bridge in a rectangular movement, the watch having been made to commemorate the 30th anniversary of Antiquorum. Other talents include Xu Shu Ma and Lin Yong Hua, who are current members of the AHCI and often present their vision of Chinese horology to the world during trade shows.

Final Thought

Whilst the above coverage of watchmaking history is highly condensed, it is interesting to note, through exploring the historical timeline, how the watchmaking industry is interrelated between countries, their cultures and historical events. It is fair to say that most of them, to a certain degree, had developed a linkage centring around the horological development of Switzerland (which we explored in our first instalment). But it is not to say Swiss watchmaking is the only stage to pay attention to, as there are other locales that show promising, interesting timepieces with their skills and passion; the watch industry around the rest of the world is also a source of inspiration for those seeking more unusual talking pieces.